It was a rainy September day in Clydebank, Scotland when Britain’s King George V stepped up to the microphone. Before him was a towering steel mountain: the hull of the brand-new ship. He and his wife, Queen Mary, and the Prince of Wales were there to participate in the launching ceremony of this new Cunard-White Star superliner. To this point, the new ship had only been known as Job Number 534. Queen Mary herself would be the one to name and launch the new ocean liner.

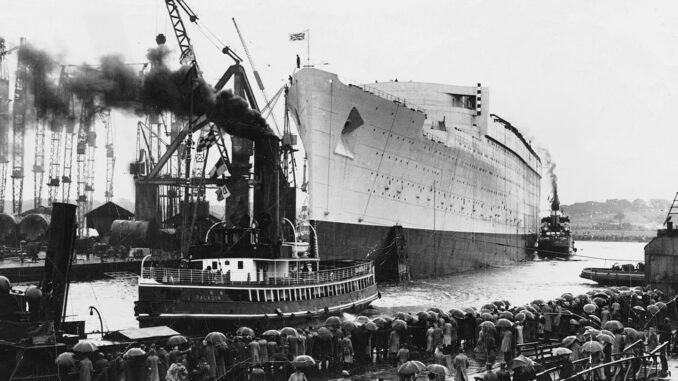

Newsreel cameras captured the momentous event as thousands crowded in close to hear the King and Queen. The entire ceremony was being broadcast across the world via wireless. Sir Percy Bates, chairman of the Cunard-White Star Line, gave the King and Queen a warm welcome.

King George V stepped up to the microphone and, reading from a prepared text, said:

I thank you for your loyal address of welcome to us. As a sailor, I have deep pleasure in coming here today to watch the launching by the Queen of this great and beautiful ship.

The sea, with her tempests, will not readily be bridled, and she is stronger than man; yet in recent times man has done much to make the struggle with her more equal. It is still less that 100 years since Samuel Cunard founded his service of small wooden paddle steamers for carrying the mails across the Atlantic to America. Those first Cunard ships were of 1,150 tons. A few people now alive must have in childhood have heard those ships spoken of with wonder of man’s evidence of mastery over nature.

Today we come to the happy task of sending on her way the stateliest ship now in being! I thank all those here and elsewhere whose efforts, however conspicuous and humble have helped to build her.

For three years her uncompleted hull has lain in silence on the stocks. We know full well what misery a silent dockyard may spread among a seaport and with what courage that misery is endured. During those years when work upon her was suspended we grieved for what that suspension meant to thousands of our people.

We rejoice that with the help of my government it has been possible to lift that cloud and to complete this ship. Now with the hope of better trade on both sides of the Atlantic let us look forward to her playing a great part in the revival of international commerce.

It has been the nation’s will that she should be completed, and today we can send her forth no longer a number on the books, but a ship with a name in the world, alive with beauty, energy and strength.

Samuel Cunard built his ships to carry the mails between the two English-speaking countries. This one is built to carry the people of the two lands in great number to and for so that they may learn to understand each other. Both are faced with similar problems and prosper and suffer together.

May she in her career bear many thousands of each race to visit the other as students and to return as friends. “We send her to her element with the goodwill of all the nations as a mark of our hope for the future. She has been built in fellowship among ourselves. May her life among great waters spread friendship among the nations.

An applause rang out, and then Queen Mary christened the ship with a bottle of Empire wine. She then stepped up to speak. This was the moment that new ship would finally receive her name.

“I am happy to name this ship the Queen Mary.” Cheers and applause broke out. “I wish success to her and all who sail in her.”

The Queen pushed a button, and her new namesake slipped into the River Clyde with the easy grace that would come to define her career. It’s estimated that 250,000 had gathered to watch the new ship’s launch that day. It’s now been 90 years since that momentous occasion, and the Queen Mary is still miraculously around.

But as the King noted, the Queen Mary was almost never completed. Her construction is a story of perseverance, compromise, and possibly even a bit of fate.

A Dream Delayed

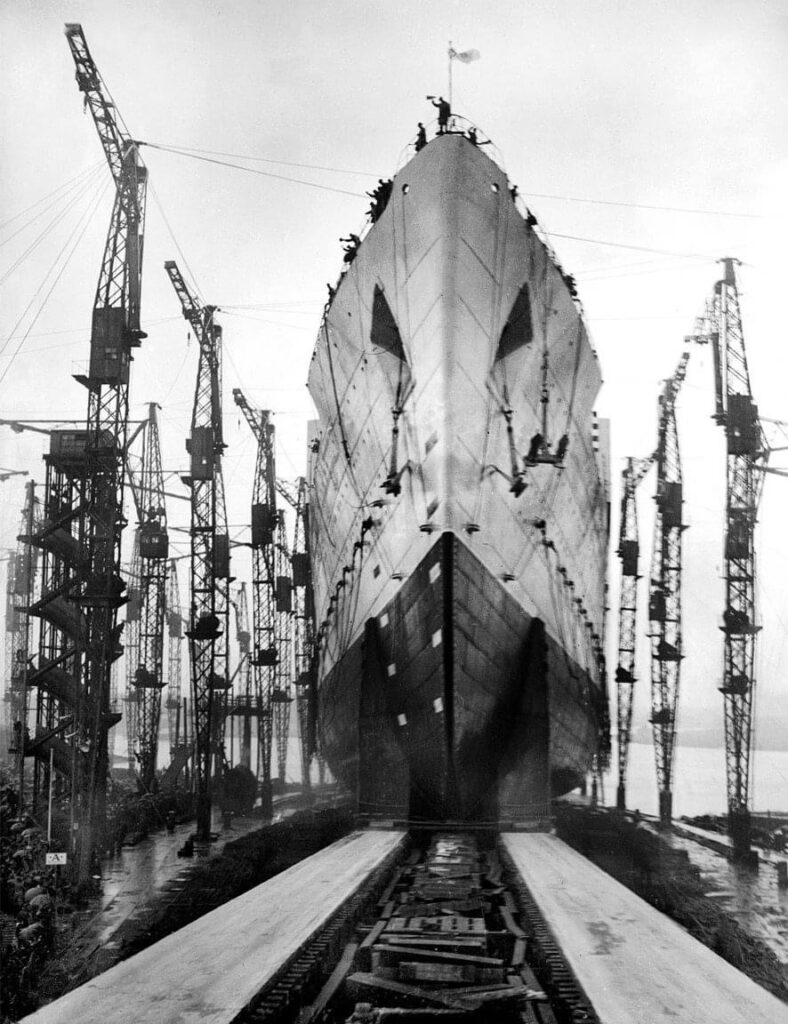

Construction on Job Number 534 started in December 1930 at the John Brown & Company shipyard in Clydebank, Scotland. The Cunard Line intended the brand-new ship to be the most magnificent afloat. It was also a direct response to the new German liners Bremen and Europa, who by that time had each captured the coveted Blue Riband (both ships won the Westbound record in 1929 and 1930 respectively, though Europa never managed to capture the Eastbound record). The record had previously been held by Cunard’s own RMS Mauretania. Gone was Great Britain’s command of the transatlantic passenger trade.

If that weren’t enough, Cunard’s great rival had almost one-upped them as well. The White Star Line had ordered a new ship that would’ve been the first 1,000-foot ship in history. The Oceanic, as she was intended to be called, would also be capable of reaching speeds of up to 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph). Construction on this new ship started at the Harland & Wolff shipyard in June 1928. However, construction was halted the following May and ultimately cancelled due to the Great Depression. As such, Job Number 534 was destined to be history’s first 1,000-foot ship.

However, the same economic issues that lead to Oceanic’s cancellation put a halt to 534’s construction in December 1931. The partially completed hull would sit gathering rust until May 1934.

A Dream Fulfilled

The Great Depression hit the Cunard Line hard. It applied for a loan to finish the ship and its proposed running mate. The British government granted £9.5 million for the project, but on the condition that Cunard merge with the White Star Line. Both companies agreed to the merger and formed the Cunard-White Star Line as a result. Work on 534 resumed almost immediately.

Just four months after construction was resumed, the new ship was ready for launch. Job Number 534 had become a symbol of British perseverance in the face of the Great Depression, and the people rallied behind its completion. The launch was set for September 26, 1934.

As Queen Mary named and launched the new ship, cheers erupted around the River Clyde. Drag chains slowed the liner down and a wave washed over the shoreline. The Queen Mary was born.

Big things were expected from this new ship. The Queen Mary was the pinnacle of British marine engineering and created through the labor of thousands of Scottish builders. It was expected that she would retake the Blue Riband for Great Britain. But the Queen Mary would also be sent to the scrapyard someday. It was a natural part of any ship’s life.

A Lasting Legacy

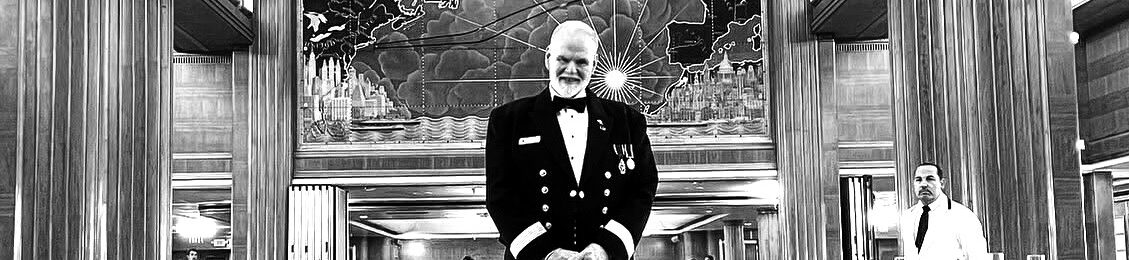

The Queen Mary is a very special ship. At 90 years old, she’s survived against incredible odds: the Great Depression, World War II, and now the COVID-19 pandemic. Every other transatlantic superliner is gone (with the exception of the SS United States). Queen Mary is the last of her kind. But she’s always been unique. The ship seems to have always possessed a certain charm that inspired good and happy feelings. Captain John Treasure Jones, the Mary’s last captain, even said that she was the closest thing to a living being that he’d ever commanded. I certainly felt it every day I went to work aboard the old ship.

Without a doubt, there’s always been something about Mary.

Leave a Reply