Wednesday, July 4, 1923 was a dull, rainy day in New York. An American monster was about to set sail and there was excitement in the air. An excited public had gathered to see the gigantic ship at Pier 86. Eager visitors snapped up the 10,000 passes in order to see the liner firsthand. A sold out voyage only added to the excitement.

This was the liner’s first civilian voyage in nine years. When the Great War broke out in July 1914, the ship and her crew sought refuge in the neutral United States. When America entered the conflict three years later, the idle German ship became a troopship. President Woodrow Wilson suggested the ship’s new name himself. The name came from a monstrous sea demon in the Old Testament; it was a name befitting her incredible size.

The Leviathan was born.

Germany’s Challenge

The Leviathan started life as the German liner SS Vaterland. Built by the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg, she was the second in a trio of massive Hamburg America liners. The first of these was the 52,117 GRT Imperator. These ships intended to assert Germany’s place on the transatlantic passenger trade and rival those of Great Britain. Had World War I not intervened, that plan may very well have succeeded.

The Vaterland was launched on April 3, 1913 in the presence of Bavaria’s Crown Prince Ruprecht. At 54,282 GRT, she was even bigger than her older sister and had a top speed of 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph). The Vaterland had the most modern safety features at the time, as well the most powerful wireless radio set at sea (courtesy of the Telefunken Company of Berlin). Her luxurious public spaces also rivaled those of the Imperator. Funnel intakes ran along the sides of the hull, which created a tremendous amount of space not common on other ships at the time. As the pinnacle of German marine engineering, the builders spared no expense on the Vaterland.

On May 14, 1914, the Vaterland set sail on her maiden voyage and arrived in New York six days later. But even as the world celebrated the new liner as an engineering marvel, war in Europe was brewing and erupted the following month. Vaterland was on her fourth westbound crossing at the time, and she sought refuge in the neutral United States following her arrival.

There, she and her crew would linger for the next three years. American destroyers watched over her and other German ships to make sure they stayed put. As an added precaution, the British Royal Navy also set up a checkpoint off the coast of New York. The Vaterland wasn’t going anywhere.

Wartime Service

The United States officially entered World War I on April 6, 1917. It seized and repurposed German assets. Vaterland’s crew was ordered to render the ship unusable to the Americans, but they couldn’t bring themselves to do it. They loved their ship too much to wreck and ruin her. So, the Vaterland became part of the United States Navy on July 25, 1917.

As previously mentioned, President Woodrow Wilson suggested the ship’s new name. The Vaterland officially became the USS Leviathan on September 6, 1917. The ship’s conversion into a troop transport took seven months. Leviathan’s first wartime voyage took place that December.

The gigantic ship made a total of 19 crossings between Hoboken, New Jersey and Brest, France. Conditions were cramped and crowded aboard: she regularly carried more than 10,000 soldiers. Disease ran rampant in these close quarters. As it happened, it was during this time that the Great Influenza struck the unsuspecting global population. Between 25 to 50 million died of the disease between 1918 and 1920. Unsurprisingly, the influenza pandemic reached the USS Leviathan: in one instance from September 1918, 2,000 soldiers got sick while another 80 died.

By the time the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, the USS Leviathan had brought over 110,000 American soldiers to Europe. Then she went to work bringing them home. This continued until September 1919.

Returned to Hoboken, the Leviathan sat idle once again. At last in 1922, workers started refitting the liner for passenger service. The future designer of the SS America and SS United States, William Francis Gibbs, oversaw this work. The ship’s overhaul took place at Newport News, Virginia over a period of 14 months. But there was a small problem. Because the Blohm & Voss shipyard demanded over $1 million for the ship’s blueprints, the Americans didn’t have a set to work from. So Gibbs’ draftsmen documented every inch of the Leviathan. This allowed Gibbs to draw up his own set of blueprints for the ship.

The Leviathan was reborn.

America’s Flagship

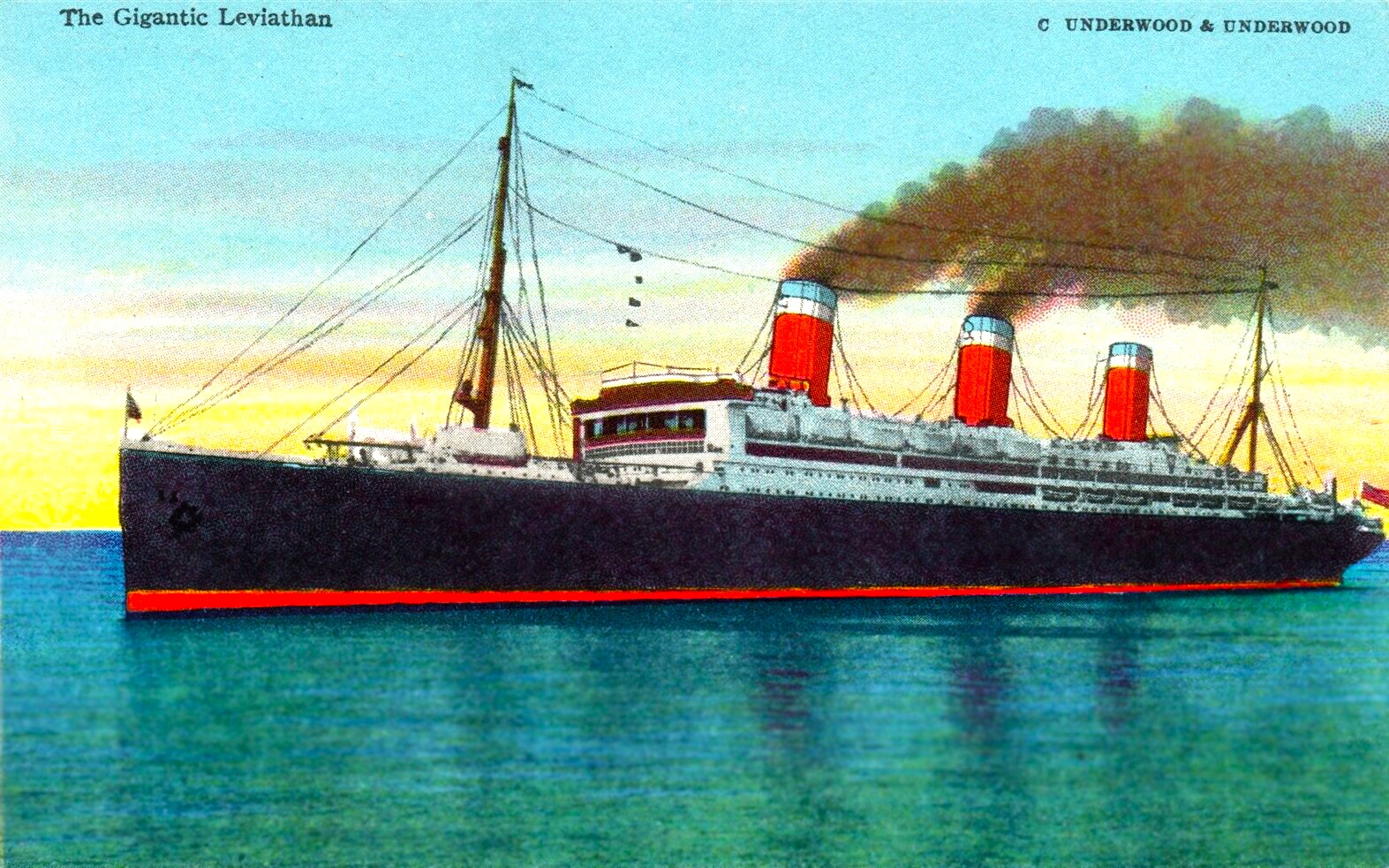

The war now behind her, the ex-Vaterland resumed her intended career. The SS Leviathan was resplendent in red, white, and blue funnels that stood out against the grey day of her maiden voyage. Her spacious interiors were lavishly refurbished and retained much of their pre-war elegance. Things were looking good for this new American flagship.

However, Leviathan was ultimately a failure.

As the 1920s went on, the transatlantic passenger trade dramatically changed. Changes in American immigration policy greatly reduced the numbers of foreigners allowed into the isolationist nation. Ocean liners’ primary purpose to that point was to carry immigrants between Europe and America.

Then the 18th Amendment was enacted, which prohibited the consumption of alcohol in 1920. This eventually meant problems for the Leviathan.

Prohibition stipulated that US-registered ships were an extension of American territory. This meant that the SS Leviathan would be a dry ship. Americans looking for a drink could sail on the other virtually identical Imperator-class ships: Cunard’s RMS Berengaria (ex-Imperator) and White Star’s RMS Majestic (ex-Bismarck). Leviathan’s older and younger sister both gained a reputation for being more fun to sail on. That said, the new American flagship found itself popular with more conservative-minded passengers.

Alcohol finally made its way onboard in 1929. It was determined that “the 18th Amendment applied only to the territorial waters of the U. S. for domestic as well as foreign ships.” Leviathan carried 97 gallons of wine and spirits for “medicinal purposes.” The ship’s passengers could eventually buy alcohol once Leviathan entered international waters.

Prohibition wasn’t the only problem, however.

At the time, there was no other American ship that could match Leviathan for size and speed. This meant the United States Lines could only offer a monthly transatlantic service, whereas Cunard and White Star both offered weekly crossings. This put the ex-Vaterland at a serious financial disadvantage, which only compounded as time went on.

The United States Lines merged with the American Merchant Lines in early 1929. It was mandated that the new company operate its ships for 10 years, and with a minimum of 61 voyages per year. The International Mercantile Marine (IMM) acquired the ship in late 1931 and reincorporated the United States Lines. But the Great Depression proved to be the grand ship’s death knell.

The Death of the Leviathan

Coupled with high operational costs, the Leviathan was losing money at a fast rate. She never made a profit for her owners and the United States Lines always seemed to be drowning in debt. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 only made matters worse. By 1933, the Leviathan was losing an estimated $75,000 per roundtrip and laid up once again in Hoboken. The United States Lines told the federal government to either take the ship back or subsidize its operation. The Department of Commerce responded with orders to put the ship back in service. Furthermore, Leviathan needed to complete five more roundtrip crossings. The ship underwent a $150,000 refurbishment and fulfilled this obligation.

With the Great Depression raging, financial matters only got worse for Leviathan and her owners. The ship lost $143,000 in 1934 alone and sailed at barely half capacity each voyage. The United States Lines eventually paid the United States government $500,000 for the privilege of retiring the liner. They actively maintained her until 1936.

The Leviathan was sold for scrap in 1937. The ship set sail on January 26, 1938 and made her way across the Atlantic one last time. She arrived in Rosyth, Scotland on February 14. Due to the Leviathan’s massive size and the onset of World War II, final scrapping wasn’t finished until 1946.

The SS Leviathan was the United States’ first superliner. She was a bold attempt to compete with the well-established British and European steamship lines. Although undeniably a financial failure, she eventually paved the way for more successful ships like the SS America and SS United States. Moreover, William Francis Gibbs cut his teeth on the Leviathan. It was no small feat to reverse engineer one of the biggest and most complex ships in the world.

In the end, the Leviathan was an attempt at something new for the United States. Many people felt that transatlantic luxury should be left to the British and Europeans. Eventually the United States Lines learned from its mistakes. America eventually became a major player in the transatlantic passenger trade in the 1940s and 1950s. And it all started with one German-built ship.

The Leviathan is not a liner to be forgotten. Ever.

Leave a Reply