Hello everyone! Apologies for the lack of posts lately. There’s been a lot going on lately, including me transitioning into a new job at work. Then there’s that dreaded writer’s block too. So unfortunately, I’ve not been able to keep up with this blog as much as I would like.

But recent events have inspired me. With Carnival Freedom’s funnel catching fire for the second time in two years, I got to thinking about weird coincidences at sea. I’ve grown up reading and hearing about strange sea stories and love them. So today I’d like to share with you five coincidences that might make you scratch your head and go, “Huh.”

5. The Death of Commodore Sir James Charles

Is there something about the sea that warns its servants of their coming deaths?

Cunard’s Commodore Sir James Charles was a charmingly affable mariner whose name became synonymous with the RMS Aquitania during much of the 1920s. He was a seaman of the highest caliber, and future Commodore Robert G. Thelwell summarized him as “the most remarkable man I served under in my life at sea.” As Sir James neared his retirement in 1928, however, he began to have a premonition that he would die at sea. He even went so far as to buy a burial plot before his last voyage aboard “The Ship Beautiful.”

As Aquitania neared Europe in mid-July 1928, the Commodore murmured, “I never realized how hard the parting would be” to his staff captain. Sir James was convinced of his imminent death.

Thelwell, a junior officer on that voyage, describes what happened at Cherbourg, France on July 15, 1928:

[Sir James] was obviously unwell but refused the pleas of his officers and the doctor to leave the bridge. He docked the ship but immediately had a severe internal hæmorrhage. On the short passage from Cherbourg he became worse and he was carried down the gangway unconscious at Southampton with only a few hours to live. He was a truly modest man. His headstone in the churchyard of the little village of Netley Marsh in the New Forest bears only his name and the dates of his birth and death.

It seems that the Commodore’s premonition was indeed correct. Sir James Charles had been due to retire from the Cunard Line less than a month later.

4. Francesca Rettondini and the Costa Concordia

It’s often said that art imitates life. But what about when life imitates art?

The Costa Concordia struck a rock formation off Giglio Island on January 13, 2012 with over 5,000 people aboard. Its captain, Francesco Schettino, famously abandoned ship while hundreds were still aboard the stricken cruise ship and in need of rescue (he’s now in prison for his role in the disaster). One of these passengers was Italian actress Francesca Rettondini. Ten years earlier, she appeared in the horror film Ghost Ship (2002) as a lounge singer named Francesca. The movie took place aboard an Italian ocean liner that disappeared in the 1960s.

Naturally, Rettondini’s experiences aboard the Costa Concordia drew comparisons to Ghost Ship. When asked about it, she said, “But that was just fiction. Tonight’s [disaster] was a tragic reality.”

In an interview after the disaster, Rettondini recounted her experiences that night aboard the Costa Concordia:

I was like a fool. I didn’t know what to do. I was scared, we all pushed towards the exit. People were panicking. When the ship tilted more and more everyone put their feet up, I was afraid to go down (…) I was lucky. But yes, come on, I was lucky because we were in the dining room when it all happened. And the luckiest ones because then we went out on deck 3, the one closest to the stern, so farthest from the water. While we were having dinner the ship made like a leap backwards. We all fell, the tables overturned, there was blood everywhere, because we were cutting ourselves with crockery. We went out on deck and they immediately let us down the lifeboats.

I didn’t know what to do. There were no staff, but it wasn’t because they didn’t want to help us. They knew we were safe and went to those in need. They were very good. But I didn’t understand the captain’s attitude. In all that hubbub, at one point he said from the loudspeakers that everything was under control, to go back to the cabins. I don’t understand anything about ships. It was my first cruise. But I didn’t want to move from where I was. I told everybody: ‘I’m not moving from here.’ Many, on the other hand, followed that advice and we never saw them again.

To be quite honest, I only recently learned that Francesca Rettondini was aboard the Costa Concordia that night. I immediately told my wife about it (Ghost Ship is a personal favorite movie of ours). Her reaction was, and I quote, “Holy sh*t!”

3. The Carmania Sinks the Carmania

Yes, I know this sounds like something out of Inception but bear with me.

Ocean liners of all nations served during World War I. They became troop transports and hospital ships, but some were also converted into auxiliary cruisers. Armed with deck guns, these ships received orders to go out and fight like warships.

On September 14, 1914, two converted liners would do battle with each other off the coast of Trinidade Island. The result? It was the first battle between ocean liners, and the Carmania was sunk by the Carmania.

Germany’s Hamburg Süd liner Cap Trafalgar was converted into a cruiser, but also repainted in the Cunard Line’s livery and specifically disguised as the RMS Carmania. Why? To try and draw out unsuspecting Allied ships with a false flag operation. To complete the illusion, Cap Trafalgar’s third funnel was also removed. The German ruse might have worked if the ship they ended up encountering hadn’t been the real Carmania, herself converted into an auxiliary cruiser.

There’s a story that the Carmania herself was disguised as the Cap Trafalgar. When the two ships met at sea, confusion reigned as each ship identified itself as the other. It’s a good story, but it unfortunately isn’t true. The British knew that Cap Trafalgar was operating in the area when they encountered each other at midday in the South Atlantic.

What followed was a brutal two-hour battle in which each ship tried to pound the other into submission. Both ships suffered heavy damage. However, despite having her bridge smashed, being hit 79 times, and catching fire, the real Carmania managed to sink the fake Carmania. The British lost nine sailors, while the Germans lost between 16-51. A total of 279 were pulled from the water after Cap Trafalgar sank.

2. The Titanic Disaster Predicted?

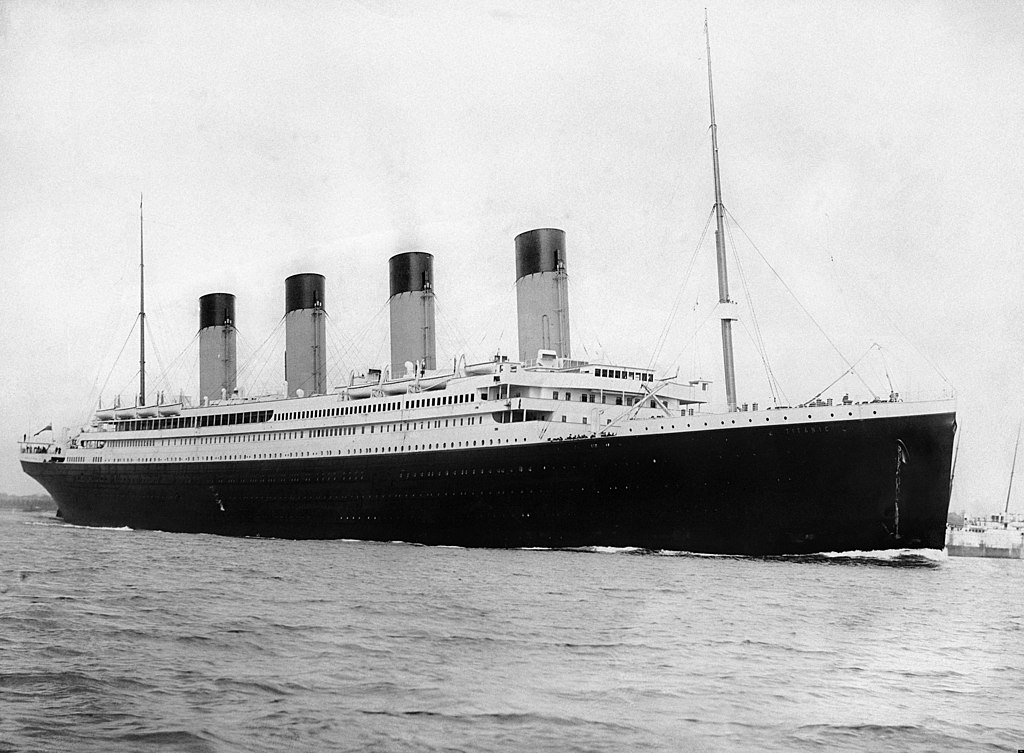

A behemoth luxury liner sails through the icy North Atlantic on a cold April night. Her triple screws turn hundreds of times per second and give her a speed of about 25 knots. Her state-of-the-art safety features have led people to call her “unsinkable.” However, tragedy strikes when the ship hits an iceberg with 3,000 people aboard. There is tremendous loss of life because the ship didn’t have enough lifeboats for everyone onboard. It is an unparalleled maritime tragedy.

This ship, of course, was the Titan. It featured in American author Morgan Robertson’s 1898 novella Futility. It was published14 years before the Titanic sank under almost identical circumstances.

After the Titanic sank on April 15, 1912, people pointed to Robertson and said he was clairvoyant and predicted the disaster. He strongly denied this. An experienced sailor who followed maritime trends, he saw how ships were getting bigger and how people were putting too much faith in technology. Robertson likely felt that it was only a matter of time until one of these monster ships sank with heavy losses. Icebergs seem to have been a particular concern.

But Futility wasn’t the only work that “predicted” the Titanic disaster. American newspaper editor and Spiritualist W.T. Stead wrote two stories that also had eerie similarities to the future events of April 15, 1912.

In 1886, Stead published “How the Mail Steamer went down in Mid Atlantic by a Survivor.” In the story, an unnamed passenger liner collides with another ship in a heavy fog. There aren’t enough lifeboats aboard, and panic ensues as hundreds die in the disaster. Stead adds at the end, “This is exactly what might take place and will take place if liners are sent to sea short of boats.” He followed this up with a short story called “From the Old World to the New” in 1892. A ship called the Majestic rescues survivors of another ship that had sunk following a collision with an iceberg.

W.T. Stead was aboard the Titanic and died in the disaster. His body was never recovered.

Were Robertson and Stead just keen observers of maritime trends and used reason and logic in their stories? Or was there something supernatural guiding their writings? Or was it all purely coincidence?

1. Violet Jessop and the Olympic-class Liners

What do the Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic all have in common (aside from being sister ships)? A young Irish-Argentine woman named Violet Jessop. Whether fate or coincidence, she happened to be aboard all three ships at pivotal moments in their careers.

Violet Jessop began working aboard ocean liners in 1908 as a stewardess for the Royal Mail Line. She later joined the White Star Line in 1911 and joined the crew of the new RMS Olympic. She was aboard on September 20, 1911 when it collided with the British warship HMS Hawke. Suction from Olympic’s massive size drew the Hawke into her starboard side, resulting in significant damage to both ships. Captain Edward Smith, in command of the White Star flagship, ordered his ship back to Southampton.

A similar episode to the Hawke collision played out the following year aboard Titanic. The American Line’s SS New York narrowly avoided a collision with the new White Star ship as it was leaving Southampton on April 10, 1912. Suction from the Titanic drew the New York in as with the Hawke. Captain Smith, having learned from the year before, ordered the port propellor reversed and avoided a collision. Violet Jessop was also aboard after being transferred to Titanic from Olympic.

After Titanic hit the iceberg late in the evening on April 14, 1912, Jessop was ordered into lifeboat 16 and given a baby to take care of. Once rescued and aboard RMS Carpathia, a woman grabbed the baby from her and ran off. Jessop returned to the UK and was back at sea shortly thereafter.

When World War I broke out, Violet Jessop joined the British Red Cross. To her amazement, she was assigned to the biggest hospital ship afloat: HMHS Britannic, the youngest sister of Olympic and Titanic. Jessop tended the wounded until November 21, 1916, when the ship struck an underwater mine in the Aegean Sea and sank. Jessop had been aboard one of two lifeboats prematurely launched and drawn into the ship’s still spinning propellors. Jumping out of the doomed lifeboat in time, she suffered a traumatic head injury but survived.

After three years of recovery, Violet Jessop returned to sea as a stewardess for the White Star Line and found herself back aboard Olympic. She eventually went to work for the Red Star Line, and then rejoined the Royal Mail Line. After a long career, Jessop retired in 1950; she had no further incidents at sea after the Britannic. She passed away at the age of 83 in 1971.

Leave a Reply